A History of Las Colinas

“We are merely the custodians of this property during its important stage of development. None of us can take it with us into immortality, so let’s resist the attitude of some real estate developers in the past to squeeze out the ‘very last short-term dollar.’ Instead, remember that generations of others who will make Las Colinas their home (both business and personal) will follow us. Let them look back and reflect on the fine effort made by those who were its custodians during the development stage.”

Memo to his staff, June 1974

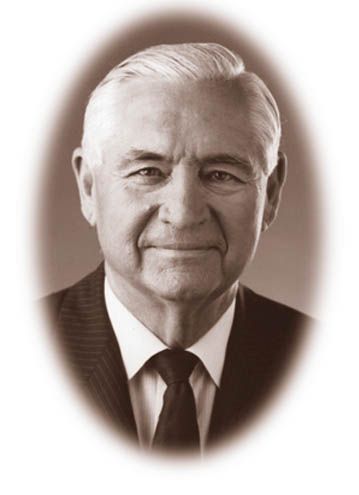

Perhaps you never met Ben Carpenter, but if you have ever glimpsed Las Colinas, you have experienced him. His imprints are everywhere. Carpenter was a man whose standards were uncompromising, and he had a deep appreciation for beauty, quality, and cohesion. Once you enter Las Colinas, it is as if you’ve crossed an invisible line that delineates new territory. The surroundings speak for themselves. Buildings and homes are unique in character, yet harmonious with the environment and each other. The same level of quality is pursued in all common areas, medians, and parks. Carpenter was also inspired by art and culture that spanned the globe, and he was a master at infusing exotic elements into the native landscape of Texas.

The influence of his travels is reflected throughout the community. The idea behind the Mustangs of Las Colinas originated from Johannesburg, South Africa.

The Flower Clock and canals are replications of what he encountered in Italy. Even the most enduring, distinguishing element of Las Colinas, the protection offered by deed restrictions, is an adaptation from a city he visited in the heart of Brazil’s rainforest.

Las Colinas, with its humble beginnings as a cattle ranch, has grown exponentially in size with an ever-increasing base of commercial and residential development. It is internationally recognized as a model for master-planned communities. Dignitaries from around the world still visit, hoping to capture the essence of what is Ben Carpenter’s greatest legacy.

We live, we work, and we play in a place like no other, and our lives are enriched because of it. Ben H. Carpenter, the man, will be missed, but his life will always be celebrated in these hills called Las Colinas.

The Story of Las Colinas is the Stuff of Legend

Teenaged Ben Carpenter and friends riding bulls on the ranch.

Children in grades one through seven attended the one-room Hackberry School, which was

located just northeast of the present-day intersection of Royal Lane and MacArthur Boulevard.

Chapter 1: The Ranch

‘America’s Premier Address’ had its beginning as a remote family retreat

Fate, vision and a family fortune came together to create one of the world’s premier corporate communities in a place where, only a few decades earlier, cattlemen held sway. Planned and executed with impeccable quality and consistency, the dream belonged to one man.

He brought his vision to life, nurtured it through nearly two decades, and ultimately lost control of it. During Las Colinas’ brief history, there have been glories and grief, booms and busts, struggles and transformations.

But before all those, there was the land. Before skyscrapers lined man-made lakes, before gated enclaves secluded multimillion-dollar mansions, before corporate executives sealed deals on manicured golf courses, there was wild, open land. Cattle grazed on rolling hills and grassy plains. Crops were grown in the bottom land of creeks. And families thrived or made do. One of those families would look into the future and make history: the Carpenters, who owned a place called Hackberry Creek Ranch.

John W. Carpenter bought the original holding, a few hundred acres, in 1928. Before the post-World War II boom spread highways and cities in all directions, the ranch was remote. Hackberry Creek flowed through the land, which lay near the present-day intersection of Northwest Highway and SH 114 — the John W. Carpenter Freeway. Some of the roads that led to it from Dallas and Irving were paved; many were gravel or dirt. Irving was a small rural community. Children from area farms and ranches were educated in a one-room schoolhouse, Hackberry School. Cotton was a staple crop. Wildlife, including deer, coyotes, wolves and bobcats, was abundant. The land was not yet real estate; it was the center of life.

John Carpenter was on his way to

making his fortune in electric utilities and life

insurance, and had become president of Texas

Power & Light Company in 1927. Nonetheless,

he was deeply rooted in country life. He owned several properties in rural Navarro County and over the years would buy and run a string of farms and ranches in North, East and

Central Texas. But it was the land in northwest Dallas County, however, that he chose for his family’s mooring.

With his wife, Flossie Gardner Carpenter, John was rearing his children John, Jr.; Carolyn; and Ben in Highland Park.

Hackberry Creek, while always a working ranch, was also a weekend getaway and summer retreat. The Carpenters used the ranch to

teach their children lessons about rural life. An unflagging work ethic had played a big part in John’s rise to success, and though

they were wealthy, he and Flossie wanted their children to know the importance of hard work. Flossie gave an affectionate name to

the land where her family thrived: El Ranchito de las Colinas — the Little Ranch in the Hills.

Ben Carpenter was four years old when his father bought the property. As he grew older, he worked cattle, jacks and mules

alongside the ranch hands. He wandered the open prairie. He practiced his rodeo skills with friends. And like his parents, Ben loved

the land.

Four decades later, when development of the land became inevitable, that love would shape Las Colinas: Ben created lakes

and canals that followed the path of existing creeks. He built the Las Colinas Equestrian Center and deed-restricted it to ensure its

continuity. And he left fully one-third of the development’s land as open space.

By 1948, John Carpenter, Sr. had bought neighboring properties, expanding the ranch to nearly 1,500 acres. Ben, who had

returned from his service in World War II, completed his degree in Business Administration at the University of Texas and married

Elizabeth Ann Dupree, who was called Betty. The couple moved to Hackberry Creek Ranch, settling in a house on the property’s

highest hill, and there they reared their five children.

Development was beginning to move outward from Dallas and Irving, crawling slowly toward them. While the ranch was

still remote, it wouldn’t remain that way much longer.

Ben and Betty Carpenter lived on Hackberry Creek Ranch for 49 years. During that time, the land was transformed from

open country, where livestock had to be protected from coyotes and wild dogs, to a corporate mecca of unparalleled quality and

reputation. When faced with the inevitable, Ben took fate by the hand and turned his beloved ranchito into Las Colinas.

Chapter 2: Men of Vision

Two generations of Carpenters shaped their worlds with insight and determination

In building this world-renowned community, Ben Carpenter was determined and indefatigable. Conversely, he also was

modest and content to stay out of the limelight, a man who preferred to let his accomplishments speak for him. He came by these

traits naturally: Ben was the son of a man whose own vision and drive helped bring Texas out of Reconstruction

and into the modern era, a man who valued deed above reputation.

John W. Carpenter came of age at a time when Texas was at a crossroads. Born in 1881, only seven years

after Reconstruction had come to an end in the state, John was reared by parents who had lost everything in the

Civil War and moved from Tennessee to Texas in a covered wagon. They settled on a farm in Navarro County.

John left the farm in 1900 to support his mother and five sisters after his father’s death, taking a job as a laborer at

Corsicana Gas and Electric Company.

The electric utility industry was in its infancy, and Texas was still a rural state. Thomas Edison had made

the first practical light bulb only 21 years earlier. Utility companies were small, privately owned, independent

operations. They frequently served one town with a single generator, running at night and one morning a week.

John Carpenter embraced the nascent electric utility industry as the foundation for diversifying Texas’ economy, leading it

past the legacy of the Civil War and of Reconstruction policies that had stifled its development. John devoted himself to his work,

giving “a full day’s work for a full day’s pay,” taking correspondence courses, and completing an elite General Electric apprenticeship

in New York. Seven years after he started digging post holes for Corsicana Gas and Electric, he became the company’s

president.

In 1918 he came to Dallas as vice president and general manager of Dallas Power and Light. Two years later, he was vice

president and general manager of Texas Power and Light, which was acquiring small-town utility companies and consolidating them

into a single regional firm. He became president of TP&L in 1927. Under his leadership, the company developed the region’s

distribution grid and grew to serve a territory of more than 50,000 square miles in North, East and Central Texas.

John Carpenter believed that business existed to improve people’s lives, to increase prosperity and employment

opportunities. And he was dedicated to making life better in TP&L’s service area, in part by diversifying the region’s economy:

He was a leader in the rural electrification effort in the United States. He championed improved farming methods. And he

advocated for flood control on Texas rivers, which would allow both agriculture and business to prosper. To this end, he organized

the Trinity Improvement Association to develop dams and reservoirs along the unpredictable river’s course.

Because of his belief in self-reliance, he founded the Texas Security Life

Insurance Company, the nucleus of the company that later became Southland

Financial, the parent of Las Colinas Corporation. And he organized Lone Star Steel

in East Texas to support the World War II effort and bring the steel industry, which

Northern industrialists had kept a tight rein on, to Texas. His civic involvement

ranged from bank directorships to spearheading the creation of the State Fair of

Texas.

Throughout his life, he never strayed from his country roots or lost his love

of the land.

Like his father, Ben Carpenter was as comfortable on a cattle ranch as he

was in a board room. And also like his father, he conducted his business with

integrity, energy, vision and a belief that his life should be lived to benefit society.

Ben was born in 1924. The pivotal experience of his life was the Carpenter

family’s only tragedy: His older brother, John, Jr., then a 19-year-old freshman at the

University of Texas, was killed in a car accident. When the mantle of the great father

fell on the younger son, Ben accepted it and proved himself a worthy successor.

A high achiever and natural leader from an early age, Ben was a ranch

foreman at 15, a published author while still in high school, and a recognized

livestock authority in college. As a 20-year-old second lieutenant in World War II’s

China-India-Burma theater, he received the Silver Star for taking command, after the officer in charge deserted, of three platoons that were surrounded by Japanese troops and under heavy artillery fire. Under Ben’s

leadership, they won the battle.

After the war, Ben returned to Dallas to become president of the Crockett Company, a Southland Life affiliate. Later, he

took the helm of Southland Life and Southland Financial Corporation. He continued his father’s work with the Trinity River, serving

as president of the Trinity Improvement Association and the Trinity River Authority. An avid rancher as well as businessman, he

held a six-year term as president of the powerful Texas and Southwest Cattle Raisers Association.

Ben H. Carpenter

A young Ben Carpenter receives the Silver Star

Medal for bravery in battle.

Ben possessed an exceptional intelligence, a powerful sense of fairness and a strong dislike of politics. He was headstrong

but open minded, wanting — and almost always getting — things done his way. And he had an inordinate ability to manage details

while maintaining a panoramic view: In building Las Colinas, Ben’s eye fell on points as fine as the Urban Center’s granite curbs and

the quality of the patina on the surface of The Mustangs of Las Colinas.

Both John W. and Ben Carpenter saw the world not only as it was, but as it could be. For the younger Carpenter, the view

encompassed the post-World War II boom and the coming of Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport.

His challenge was to take the resources he had and use them to create something of lasting value and benefit to the North

Texas region and its people. The result is his legacy: Las Colinas.

Chapter 3: The Coming Growth

Carpenters expand ranch, create buffer to prepare for development

Irving, once a quiet town surrounded by small farming communities, grew exponentially in the years after World War II.

As development surged northward from the fringes of the city, John and Ben Carpenter recognized the inevitability of developing

their beloved family retreat, Hackberry Creek Ranch. And while the idea of Las Colinas had not yet been conceived, the Carpenters —

men well accustomed to looking into the future and seizing the opportunities it offered — began laying the groundwork to ensure

that, when the time came, their family ranch could be developed with quality and integrity. They expanded their land holdings,

created a buffer to protect the ranch from poor-quality development and created the “front door” necessary for growth: SH 114,

the John W. Carpenter Freeway.

Irving, after the war, was poised to become a bedroom community. As the nation’s population moved outward from its

cities, small towns quickly became suburbs, and Irving was close enough to Dallas to become part of that trend. The city’s

population in 1940 was 1,089. It swelled to 2,615 in 1950, then exploded to 45,985 in 1960. It doubled again to 97,457 in 1970.

Zoning before 1964 was somewhat lax, and the growing city sprawled with little planning to stop it.

In 1950, the boundaries of Irving were the Rock Island Railroad to the north, Sixth Street to the south, Nursery Road to

the east and Delaware Creek to the west. The City had three employees, a total payroll of less than $10,000 and a street-maintenance

budget of about $300. Still, by the early 1950s, the first tentacles of sprawl were reaching toward the ranch.

Even though they hadn’t yet created a development plan, the Carpenters knew the approach they would take: First, they

would resist selling off or subdividing land. They would preserve the natural beauty of the ranch, with its gentle mesquite-covered

hills, its creeks and lakes. They would take the opportunity to create a development of extraordinary and lasting quality. Working

with Ben’s brother-in-law, Dan Williams, and Wayne Hurd, who later became the first president of Las Colinas Corporation, John

and Ben began to put the early pieces in place.

The most pressing issue was preventing undesirable development, and nipping what already existed in the bud. At the

time, most of Irving’s residents lived south of SH 183, then a two-lane road. But so-called shanties — 75 or so substandard houses, typically with outhouses and shallow wells — had grown up between 183 and the ranch. Some had been built in the 1940s on

two- to three-acre tracts. Others, including a number of urban-style shotguns, had sprung up more recently, and their growth was

accelerating.

Under the aegis of the Crockett Company, the Carpenters began buying out individual landowners in 1952, and continued

until they controlled the land — eight to 10 tracts in all — by 1957.

In 1954, John and Ben found out that another southern neighbor, Ben Johnston, the son of an Irving pioneer, planned to

sell his land to a company that manufactured concrete pipes. They also learned that the Catholic Diocese of Dallas was scouting for

a location for a new university. John showed them the Johnston’s property, which included Turkey Knob, one of the highest hills in

Dallas County. He offered to donate 150 acres of Carpenter land if the diocese would buy the Johnston’s. It agreed, and added tracts

from the neighboring McCune and Gleghorn families, 1,000 acres in all. A little more than a year later, the University of Dallas

opened, and the southern border of the ranch was secure. In 1956, the Carpenters extended it with the purchase of the 2,000-acre

O’Connor farm.

In 1959, Hackberry Creek Ranch had grown to 6,000 acres. Part of the O’Connor land was combined with the

substandard-housing tracts to develop Northgate, a neat, middle-income subdivision of about 1,500 homes. It was the first of its

kind in Irving.

The same year, John W. Carpenter died of a heart attack at age 77.

Around the time of the University of Dallas deal, the Carpenters bought land on the east side of the Elm Fork of the

Trinity River, again to squelch a wave of substandard housing. They sold part at a loss to the City of Dallas, whose western boundary

reached the river, and deeded more on the condition that the land become a golf course. It did: L.B. Houston Park, the east buffer.

Meanwhile, pressures to develop the ranch grew stronger. Property taxes rose, agricultural income remained flat, and

operating expenses increased. Irving was aggressively annexing land in the late 1950s and early 1960s, as it competed with

neighboring cities in a virtual land grab. When the City tried to annex the entire Hackberry Creek Ranch, Ben Carpenter responded

with a lawsuit. The City of Irving was unable to provide services, and most of the land could not be developed without them. City

leaders, undoubtedly realizing the tax-generating potential of the Carpenter land and the wisdom of cooperating with Ben, agreed to

annex the land in sections.

The Crockett Company began developing

University Hills, a larger and more upscale subdivision than

Northgate, in 1963. The Las Colinas Country Club opened in

1964 in the middle of a pasture on the ranch. Even though

the club was so remote that the only other building in sight

was the Carpenters’ house, nearly three miles away, the list of

founding members reads like a who’s who of Dallas-Fort

Worth power brokers: Amon Carter, Jr.; Trammell Crow;

Robert Cullum; J. Erik Johnson; Clint Murchison, Jr.; John

Stemmons; R.L. Thornton. The country club, designed for

successful businessmen and anchored in the beauty of the

ranch’s rolling hills, set the tone for future development.

Las Colinas’ “front door” — the means of access to

provide “location, location, location” where none existed —

was on its way. In the early 1950s, John Carpenter had

envisioned a freeway system linking Dallas and Denton and,

along with John Stemmons and Brookhollow Industrial

District developer Bill Windsor, in 1952 donated land for its right-of-way. This land helped define the course of I-35E, which was

built a few years later as part of the federal government’s push to create a national freeway system. When I-35E was constructed, SH

114 was rerouted from what is now Spur 348 to its present course. It opened in 1972 as the John W. Carpenter Freeway.

Another of John Carpenter’s visions for North Texas was a regional airport that would serve both Dallas and Fort Worth.

In 1968, nine years after his death, the Federal Aviation Administration announced the location of the new Dallas/Fort Worth

Regional Airport — adjacent to the western edge of the expanded Hackberry Creek Ranch. The land’s value and potential increased

overnight. The time for planning Las Colinas had come.

Chapter 4: The Master Plan

After more than 20 years of preparation, Ben Carpenter’s vision takes shape

On September 14, 1973, a group of prominent Dallas-Fort Worth businessmen gathered for a luncheon in the Grand

Ballroom of the Sheraton-Dallas Hotel. They were guests of Ben Carpenter, then president and CEO of Southland Financial

Corporation and chairman of its subsidiary, Las Colinas Corporation. He had called them there to inaugurate a grand project:

That day, Ben Carpenter officially unveiled the master plan for Las Colinas.

The plan had been some five years in the making. After years of envisioning a comprehensive, high-quality development on

the 6,000 acres of land he had amassed, in 1968, Ben engaged Jim Downs of Chicago-based Real Estate Research Corporation to

perform an in-depth feasibility study. Two years later, Downs, who was considered the best in the business, pronounced the Las

Colinas acreage “one of the two most valuable and potentially promising pieces of undeveloped urban real estate in the United

States.” With his instincts confirmed, Ben moved forward with the next step: creating a master plan.

The master plan would be a “working case study,” articulating core concepts and providing a consistent but flexible framework

for development. It would assimilate Downs’ findings, determine the best use of the land and outline a strategy for implementation.

In July 1971, Ben entrusted his dream to architects Ernest J. Kump Associates of Palo Alto. Educated at Harvard and

Berkeley, Kump was a brilliant man with a boundless enthusiasm for life. He was considered the best designer of schools and college

campuses in the country. And when he took on the Las Colinas project, he had absolutely no land-planning experience.

Ben had seen Kump’s work on one of the many trips he had taken over the years to research new developments. On a trip

to Northern California, Ben fell in love with the serene and naturalistic campus of Foothill College, a Kump design that the

San Francisco Chronicle called “the most beautiful community college ever built.” When he later brought Kump to Irving to design

an elementary school for University Hills, Ben recognized the mind that could give shape to his vision. Lack of experience didn’t

matter. Creativity did.

Kump’s planning process began with exploring the land — living and breathing it — and by listening to Ben’s aspirations

and dreams. It proceeded with assembling an expert team of consultants in areas such as transportation, residential development, civil engineering and airport-noise pollution. Finally, with an understanding of the land’s possibilities and Ben Carpenter’s dreams,

Kump and his principal designers, Dale Sprankle and Bob Sprague, sat down to generate the “big idea.” From this, all other ideas

and plans would flow.

Ben put no restraints on the scope of their idea. He had enormous ambitions for the quality and impact of Las Colinas, as

well as a deep love of its land. While several key ideas were his — the Urban Center, Lake Carolyn, and the system of waterways, for

example — Ben primarily left the physical planning to others, and he gave them a free hand. His vision drove the project and set its

tone and ultimate goals: Las Colinas would be a unified community with both residential and commercial development. It would be

of absolutely the best quality, and it would embody a unique character and identity.

Ben worked closely with Ernest Kump in the beginning, then entrusted the process to Kump’s team and Las Colinas

Corporation President, Wayne Hurd, who served as Ben’s emissary. A creative and articulate man himself, Hurd ferried ideas and

designs between Ben and Kump’s team. When the “big idea” for Las Colinas was articulated, it succinctly translated Ben’s vision:

Preserve the character of the land, establish separate but interrelated communities, and create a lakeside urban center to give Las

Colinas a sense of place.

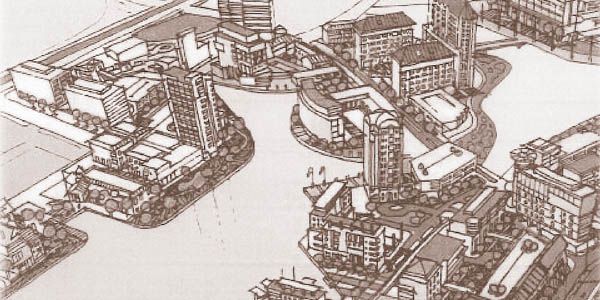

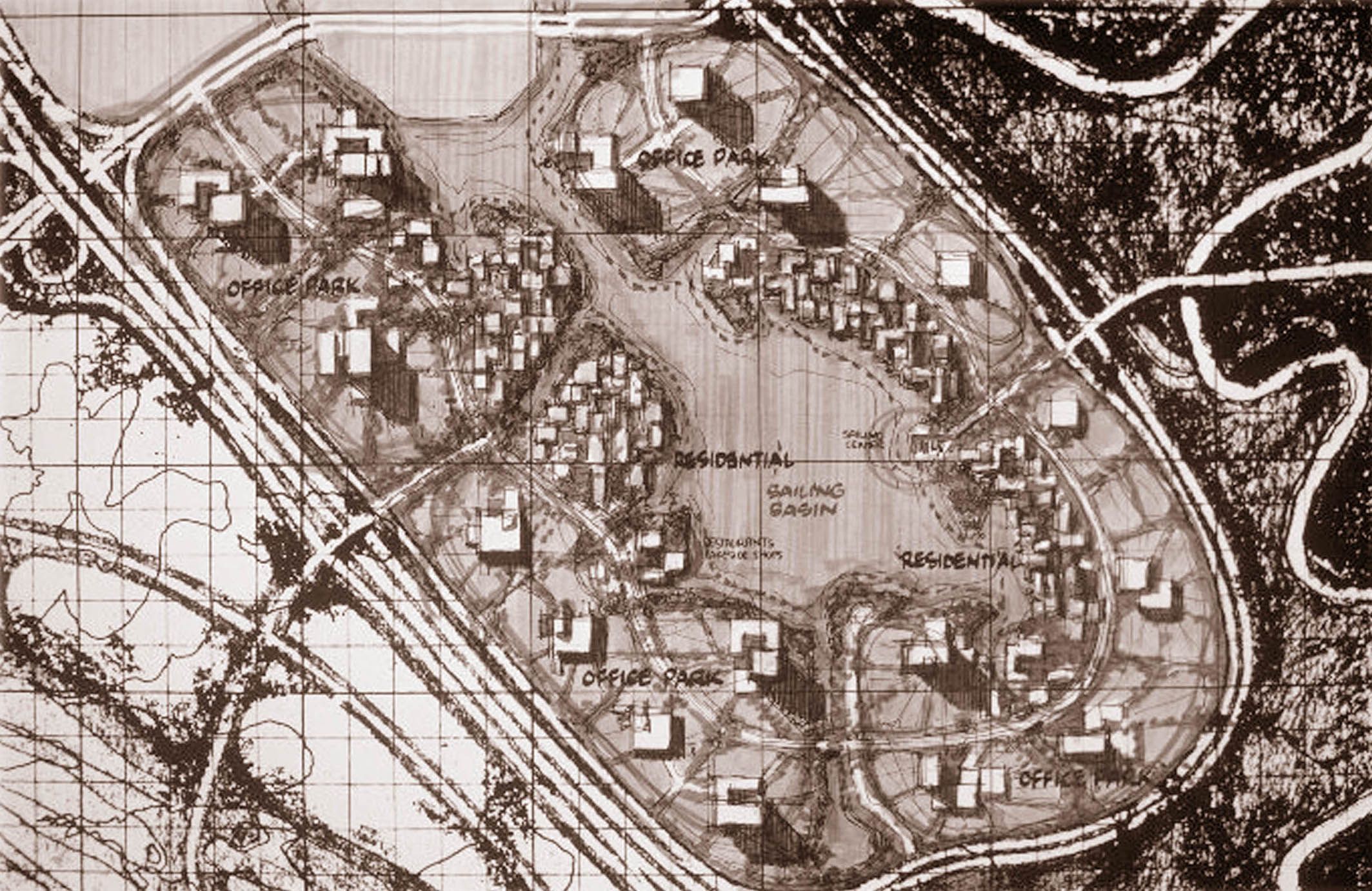

Rendering of the Urban Center from the Las Colinas master plan.

The master plan was developed during a year-and-a-half of intense work. In June 1972, when the plan had gelled but was

still incomplete, Ben and his colleagues asked a panel of prominent real estate developers from the Urban Land Institute to evaluate

it. Meeting in a five-day session at the Las Colinas Country Club, the panel pronounced the plan sound, with one ironic exception:

They believed the Urban Center was not feasible. Where Class A office towers, luxury hotels, apartments, shops and restaurants

now stand on the shores of Lake Carolyn, Urban Land panelists recommended multifamily residential, low-density office and some

service-retail development. They saw the real commercial opportunity for Las Colinas in airport-focused light-industrial

development. Ben stood by his vision.

With the completion of the master plan, all the pieces needed to create Las Colinas were in place. In the same month

Ben Carpenter revealed the master plan, construction began on $25 million in infrastructure projects, including Lake Carolyn.

Las Colinas Corporation committed to spending $750 million for improvements designed to stimulate growth over the next

15 to 20 years. And the first land buy had been made: In August 1973, Allstate Insurance purchased a 22-acre tract for its new

regional headquarters.

Las Colinas was in business.

Chapter 5: Building Infrastructure

The Las Colinas Urban Center is shaped by the creation of Lake Carolyn

With the master-planning process well under way, in 1972, Ben Carpenter turned his attention to creating two institutions

that would be cornerstones of Las Colinas’ success: a municipal utility district to create and maintain Lake Carolyn, as well as other

infrastructure projects, and a strong property owners association to enforce the quality standards he believed were key to the

development’s long-term success.

At the heart of the master plan for Las Colinas was a high-density, mixed-use urban center to be built on 960 acres that lay

east of the John W. Carpenter Freeway and south of Walnut Hill Lane. This land also lay in the floodplain of the Elm Fork of the

Trinity River and would have to be reclaimed.

Conventional reclamation methods called for a levee and bar ditches, which would be unsightly and render the land

unsuitable for the Class A development Ben had in mind for the area. But he had an ingenious solution: Dig out the center of the

land to create a deep, 125-acre lake, and use the excavated dirt to build a levee that would rise so gradually from the lake’s eastern

bank that it would be virtually unnoticeable. Thus was born Lake Carolyn, or Lago de Las Colinas, as it was originally called.

The Las Colinas Urban Center would be protected by a levee that stood 437 feet above sea level, exceeding the U.S. Corps

of Engineers’ 500-year flood elevation for that portion of the Trinity River. The land’s natural beauty would be preserved, and the

Urban Center could be built around a lake, increasing its desirability, and therefore, its value.

Likewise, Ben took a creative approach to handling storm-water runoff, with a plan that would build canals that followed

the area’s creeks, let them feed into Lake Carolyn, then direct the flow into the Trinity River at the south end of the Urban Center.

Forrest & Cotton, Las Colinas Corporation’s consulting engineer, worked out the details.

Lake Carolyn and the canals would be the biggest infrastructure project that would ever be built in Las Colinas. And

constructing them would be a significantly costlier endeavor than a conventional floodplain reclamation project.

Wayne Hurd had left Las Colinas Corporation in May 1971 to develop Horseshoe Bay, a luxury resort on Lake LBJ in the

Texas Hill Country. Faced with turning 2,700 acres of goat pasture into a first-class resort, Wayne and Norman Hurd, his partner and cousin, in October 1971

petitioned the Texas Water

Rights Commission to create

a municipal utility district

under a law that had recently

been passed by the Texas

Legislature. The new Lake

LBJ MUD was authorized to

sell bonds to finance waterrelated

infrastructure projects

and levy taxes on landowners

to pay for the improvements

and their maintenance.

Ben Carpenter

adopted his friend’s approach

for Las Colinas. By building

Lake Carolyn through a

municipal utility district, Ben

believed he could not only

substantially increase the

value of Urban Center land, but also spread out the financial burden as that land was sold and developed.

He petitioned the Texas Water Rights Commission on behalf of Las Colinas Corporation in March 1972. That June, the

Dallas County Municipal Utility District No. 1 was created. The district, which later expanded its scope and became the Dallas

County Utility and Reclamation District, or DCURD, originally comprised 1,421 acres: the 960-acre Las Colinas Urban Center and

the land on either side of Hackberry Creek.

The new district’s goals were clear: Build Lake Carolyn and make the property within its boundaries viable for

Class A development.

The first business of DCMUD was to vote to sell $24.5 million in bonds and levy taxes for their payment. Only four votes

were cast in the election, presumably by Ben and Betty Carpenter and two ranch hands. Virtually all the land in DCMUD was

owned by Las Colinas Corporation or the Carpenters, and all of it except the family’s Hackberry Creek Ranch was undeveloped.

Almost immediately, the young district issued bonds in the amount of $12.5 million to finance the construction of Lake

Carolyn and related storm-drainage and sewer projects. At the time, the assessed value of the entire district was only $14.2 million.

Holloway Construction Company of Troy, Michigan, broke ground on Lake Carolyn in the fall of 1973, shortly after the

master plan for Las Colinas was announced. Working around the clock, it took slightly more than two years to complete the lake.

It was nearly another year before it filled with water.

Ben used the master-planning period to prepare Las Colinas’ master declaration, which would serve as the base document

to regulate land use and establish the covenants, conditions and restrictions that would ensure the development’s quality forever.

The declaration was filed on August 22, 1973, with Las Colinas Corporation as the declarant, just before the Allstate land sale

closed. The declaration was written to encompass not only the existing Las Colinas acreage, but also to include any land that Ben

might purchase and add to the development in the future.

Also that day, the Las Colinas Association, the development’s property owners organization, was officially formed as a

nonprofit corporation. Much of the Association’s role was outlined in the declaration: Enforce the declaration’s terms, administer the

architectural-control process, and collect annual assessments of members, based on the value of their property. The Association

would also oversee Las Colinas’ security system and patrols, as well as maintain the development’s extensive common areas.

Ben Carpenter was its first president.

Las Colinas Corporation also had a no-holds-barred marketing plan in place and was waiting for the slow economy of the

early 1970s to improve before rolling it out. Still, interest in the development was strong, and Las Colinas Corporation and its

subsidiaries were prepared to jump-start Ben Carpenter’s dream. The first wave of growth would begin in 1975.

Chapter 6: Las Colinas Begins to Grow: 1974 - 1980

More than 130 firms arrive in Las Colinas’ first seven years

Las Colinas got off to a slow start, then quickly made up for lost time.

In September 1973, when Ben Carpenter announced his plans for Las Colinas, the United States was in a major economic

recession. By 1974, real estate prices were depressed, and tight financing had stalled new development. Southland Financial

Corporation, the parent company of Las Colinas Corporation and several other subsidiaries that would develop and market Las

Colinas, deferred rolling out an intensive marketing plan until land prices improved. Nonetheless, the cash-rich company began

spending the $750 million it had earmarked for improvements to position the fledgling development for the better times that were

sure to follow.

By the end of 1975, the company had installed streets and utilities on 627 acres, including the O’Connor Ridge Office

Center, Wingren Office Park and a number of new residential lots in University Hills. And up went the first buildings to be

developed since the Las Colinas Country Club opened in 1964. Jefferson Properties, another Southland subsidiary, completed the

332-unit Quail Run Apartments, and the first phase of the Walnut Hill Distribution Center was finished and began marketing.

North Lake College was under construction. Allstate Insurance, the first company to buy land in Las Colinas, was building its new

regional headquarters in O’Connor Ridge.

The market began to pick up in 1976. In January, The Associates North America closed on a site in Wingren Office Park,

and before the year was out, opened its new headquarters — the first office facility built in Las Colinas. Then a financial company

with $2 billion in assets, The Associates moved its headquarters from South Bend, Indiana and began to grow exponentially.

By the end of 1976, Las Colinas was home to the regional headquarters of five companies, including American Honda,

Panasonic and Agfa Gevaert. Three more office buildings were under construction, and Abbott Laboratories had signed an option

contract, which it would exercise in 1977, for a 23-acre site to house its diagnostic division. The open plains were becoming studded

with businesses. Ben Carpenter’s vision was coming to life, and his years of planning were starting to pay off.

What drew these early arrivals out from the city and onto the prairie? Although the Dallas/Fort Worth area in the early and

mid-1970s was poised for rapid growth, downtown Dallas was still the region’s commercial center, and virtually the only pockets of

office development outside it were along the Stemmons Corridor and on North Central Expressway. Suburbs were still bedroom

communities and small towns, not the employment centers most are today. When Las Colinas’ first corporate residents saw the land

for the first time, they saw not only rolling prairie, but Ben’s dream. They embraced it as their own opportunity, believed it and

invested in it.

Ben and his lieutenants were prepared to sell both Las Colinas’ concept and its land. They took prospects on helicopter

tours to show off rolling hills and future plans, then landed in front of the Las Colinas Country Club for lunch. Companies chose

Las Colinas then for the same reasons they choose it now: its proximity to the airport and downtown Dallas; accessibility; prestige;

and quality that is ensured by controls, restrictions and declarations. Prospects saw a solidly crafted master plan and a company with

the will and financial strength to carry it out.

After 1976, growth exploded. Thirteen national or regional headquarters relocated to Las Colinas in 1977, including

General Motors, Magnavox and Polaroid. GTE bought land and in 1978 occupied its new southern regional headquarters.

Construction began on Las Colinas Towers, the first office development in the Urban Center. Both towers were fully leased when

they were completed in late 1979.

Relocations continued each year. More office buildings and warehouses went up, built either by Carpenter’s companies or

developers such as Trammell Crow and the Vantage Company. By the end of 1979, more than 100 companies had begun operating

in Las Colinas, and 24 more had purchased land to develop.

By 1980, the roster of companies held 130 names, including blue-chips like IBM, Zale, DuPont, Levi-Strauss, Sony, Boeing

and Diamond Shamrock. At the end of 1980, Las Colinas had 1.9 million square feet of multi-tenant office space and another 3.4

million under construction. Southland had 765 employees in Irving.

Residential development also boomed. In 1978, University Hills sold all its available lots. Fox Glen began marketing and

sold two-thirds of its home sites by year-end 1979. Infrastructure development was underway in Cottonwood Valley. Several

apartment and condominium projects were begun.

To seed growth, Ben Carpenter began setting up Southland subsidiaries to bring services to Las Colinas that other

companies weren’t yet willing to provide. In 1979, its Metropolitan Transportation Services had 20 radio-equipped taxis serving

150 passengers a day. Las Colinas Landscape Services planted more than 700,000 flowers and shrubs, and Las Colinas Security had

its own licensed officers. Affiliated Clubs and Restaurants opened two restaurants. A new hotel division began construction on the

Mandalay Four Seasons in the Urban Center in 1980.

Las Colinas also grew in land area. In December 1976, Ben had begun purchasing land, mostly in small parcels, north of

Royal Lane. In February 1980, he bought a one-third interest in 2,400 acres known as the Byars Estate. In 1980, Las Colinas

reached 12,000 acres.

In 1981, economic conditions set the stage for what would be one of the biggest real estate booms ever. The Urban Center

was about to take shape.

Chapter 7: Building Williams Square

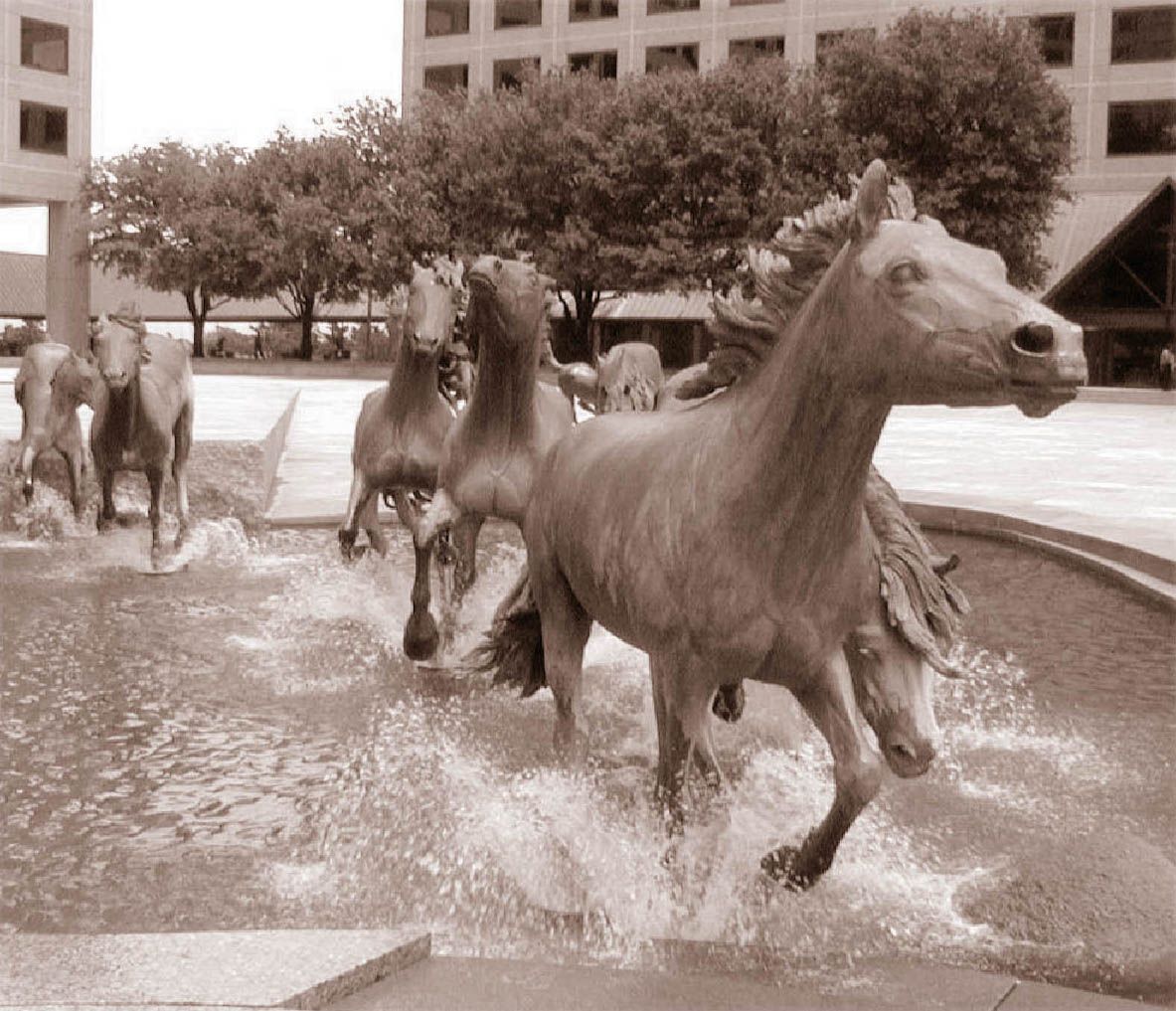

The Mustangs of Las Colinas become the development’s icon

From the beginning, Ben Carpenter envisioned anchoring Las Colinas with a monumental public space, an urban gathering

place that would become the centerpiece of his beloved new development. This vision became Williams Square, and with it, Ben

again achieved something remarkable: In the heart of the Urban Center, within the embrace of a stately 1.4 million-square-foot office

complex, Ben captured the wildness of the open Texas plains.

The Mustangs of Las Colinas, a bronze sculpture depicting nine larger-than-life horses, is the heart of Carpenter’s

centerpiece. He conceived it, and the entire Williams Square project was designed around it.

The seeds of the idea were planted in Africa, where, on one of his frequent trips to hunt big game, Ben saw a sculpture of

impalas bounding over a stream in a small Johannesburg square. Always rooted in the land, Ben envisioned a symbol of the freedom

of the plains and the independent spirit of Texas: a vast open plaza with a herd of mustangs — the wild descendants of the horses

brought by Spanish Conquistadors and missionaries to the New World — splashing across a running stream.

Ben knew wildlife sculptor Robert Glen, a Kenyan-born Scotsman who lived and worked in Nairobi, and he owned a few

of Glen’s works. In 1976, while Glen was visiting a mutual friend in Dallas, he paid a visit to Ben at Hackberry Creek Ranch.

Ben told Glen that he had an idea for a sculpture of “a herd of horses with some water,” and asked the artist to do some sketches.

Glen instead made a small scale model of six horses running through a stream, with aquarium fountain jets supplying the

water that splashed around their hooves. Two months later, when Ben saw the model in Glen’s Nairobi studio, he studied it in

silence for several minutes, then simply pointed to three places where he wanted to add more horses.

Robert Glen was a well-established artist when he took the commission from Ben Carpenter in 1977, but he had never

undertaken a project of such monumental scope. Creating nine horses at one-and-a-half times life size would take seven and a half

years of intense work.

The first year was consumed with research. Glen found that after centuries of crossbreeding, modern-day mustangs no

longer resembled their Spanish forebears. Ben found the only remaining pure strain of Andalusian horses — descendants of the sturdy breed brought to the Americas — in southern

Spain. Glen spent three weeks there studying them.

Glen’s first models for the sculpture were

small in scale, and he made 47 of them in the process of

selecting the nine that would make up the completed

piece. Then, working in plasticine, he made models at

one-half life size, or one-third the size of the finished

sculpture. They were shipped from his Nairobi studio

to the Morris Singer Foundry in Basingstoke, England,

where Glen and the foundry’s staff undertook the

complex process of scaling the pieces to full size, then

refining and casting them in bronze.

Glen completed one horse at a time, from

sculpting to casting. He didn’t see the entire piece

assembled until it was set up in a staging area in

Las Colinas shortly before its installation in

September 1984.

While Glen worked on the Mustangs, the

rest of Williams Square — the plaza and the towers —

was being designed. Ben Carpenter engaged SWA

Group, an innovative landscape architecture firm based in San Francisco, to design the plaza.

Early in the process, Jim Reeves, a principal in SWA, flew with Ben to Nairobi to see Glen’s models, and was instructed to

design the plaza around the Mustangs. He created a 300-foot-by 300-foot expanse of pink Texas granite with a “river” flowing

through the center. The plaza was purposefully left barren, like the landscape of the plains, the only vegetation a row of live oak

trees on the plaza’s east and west edges. It would be enclosed on three sides by an office complex.

Ben named the plaza to honor his sister, Carolyn Carpenter Williams, and her husband, Dan Call Williams, a former

chairman of the board of Southland Financial Corporation.

Ben hired the San Francisco office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, one of the country’s leading architecture firms, and

gave them a clear sense of what he wanted: a landmark, a grand space that would both fit in with the environment and stand out

from the other Urban Center buildings that would soon be developed.

Charles Bassett, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s senior partner, was in charge of the project. Like Ben, he was

straightforward and plain spoken, and Ben valued his skill, vision and frankness. Several designs for the office buildings were

explored before Ben settled on the final one: The Towers at Williams Square, three formal buildings, clad in pink Texas granite and

topped with copper mansard roofs, defining the plaza and facing O’Connor Boulevard.

Ground was broken in May 1981, and by January 1984, companies were moving into the partially completed buildings.

Southland Real Estate Resources, the parent company of Las Colinas Corporation, moved its headquarters to three floors of the

Central Tower. Other early tenants included IBM, which leased 10 floors in the West Tower for its national support center, and

VHA, which occupied approximately three floors in the Central Tower.

More than 20 years after its gala opening in 1985, The Towers at Williams Square is considered one of the finest suburban

office buildings in the United States. The Mustangs have become the symbol of both Las Colinas and the City of Irving, and they are

visited by thousands of people each year.

Chapter 8: The Urban Center Takes Shape: 1981 - 1986

Las Colinas matures during the real estate boom of the 1980s

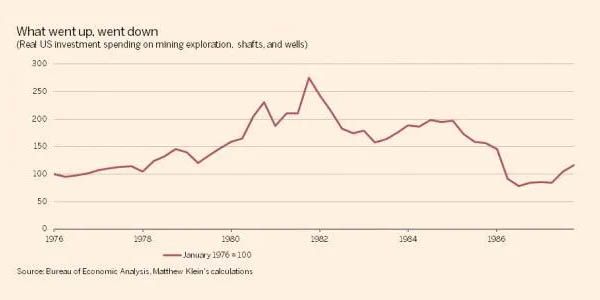

The Urban Center skyline grew up almost entirely during the early and mid-1980s, a child of the real estate boom whose

hold was particularly strong on the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex. Like much commercial real estate development of that era, it was

fueled largely by the advent of equity financing and President Ronald Reagan’s controversial economic policies.

When Reagan took office in 1981, the U.S. economy was suffering from high inflation rates, high interest rates and high

federal budget deficits. That same year he put a

cornerstone of “Reaganomics” into place: generous

tax shelters for commercial real estate. Investors

would now be able to depreciate commercial

property over only 15 years, often saving more in

taxes than the cost of the debt service on their

real assets.

At the same time, double-digit inflation

was rapidly appreciating the value of real estate,

increasing its attractiveness. Lenders were

beginning to offer 100 percent financing on new

developments in return for an equity stake. This

inadvertently relieved developers of financial risk,

and in many cases, accountability.

The Dallas area was becoming a magnet

for relocating businesses, particularly from the

North and Midwest, as companies fled to the Sun Belt. The migration spurred strong job growth. Conditions were ripe for a real estate boom, and investors and developers

were more than happy to do their part to bring it about.

What they couldn’t foresee was that the coming boom was a house of cards that would tumble down within a few years.

However, when the building halted, Las Colinas had a gleaming new downtown at its center: Between 1981 and 1988, more than

5.5 million square feet of office space was completed in 14 projects — most of them Class A high-rises.

In 1981, construction began on Caltex House, the 18-story home of Caltex Petroleum’s new world headquarters. The

company moved from New York City and occupied the building in 1982. The first phase of the Xerox Center got under way;

the second phase was completed in 1985. A third phase was planned but not built. The Towers at Williams Square broke ground

in 1981 and was completed in 1985.

1982 saw construction start on Texas

Commerce Tower and 600 Las Colinas Boulevard,

which became CIGNA’s home. The Mandalay Four

Seasons Hotel, developed by Southland Financial,

opened in August of that year.

Other office buildings rose as well:

Las Colinas Tower IV, Waterway Tower and Canal

Plaza, Waterside Commons, 511 John Carpenter

Freeway. The last to open was the Computer

Associates Tower, which broke ground in 1985

and opened in 1988.

The Las Colinas Urban Center was built

by a veritable who’s who of developers. In addition

to Southland Financial, the list included Lincoln

Property Company, Homart Development

(a subsidiary of Sears), Rosewood Properties, Henry S. Miller Co. and Xerox Realty Corporation. Trammell Crow was particularly enamored of Las Colinas: He developed five

Urban Center buildings, in addition to several industrial properties. He was overheard at the opening of The Associates building in

1976 telling Associates CEO Reece Overcash, “Look at all that wonderful land out there. I’d buy every inch of it if I could get

someone to loan me the money!”

By 1982, more than 20 shops were open along the Urban Center’s Mandalay Canal Walk. The Studios at Las Colinas

opened that year, and the Equestrian Center greeted its first riders and hosted its first annual Las Colinas Grand Prix.

Other areas of Las Colinas boomed as well. Across John Carpenter Freeway from the Urban Center, Wingren Park grew,

welcoming Gifford Hill to the new Plaza at Las Colinas and the Associates to its new headquarters, International Place. The

Associates’ new home tripled its Las Colinas presence. The Las Colinas Office Center added a number of high-quality Class B

high-rises, particularly along Greenway Drive.

Retail centers sprang up throughout the development, and residential growth continued. Country Club Place opened as

Las Colinas’ first condominium project, and Cottonwood Valley became the most chic of Las Colinas’ residential villages. The

Sports Club opened in 1983 and hosted its first Byron Nelson Golf Classic; the Inn and Conference Center followed in 1985. Both

later became the Four Seasons Resort and Club.

Las Colinas Urban Center’s first buildings in 1975.

Las Colinas’ skyline shows substantial growth of the Urban Center circa 1985.

In 1983, Las Colinas Corporation sold $100 million of land. In 1984, Las Colinas registered almost 20 percent of the

Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex’s absorption of office space — 1.8 million square feet — even though it accounted for only 10 percent

of the area’s multi-tenant office space. By 1985, Las Colinas was the third-largest Metroplex office market and the area’s secondlargest

single-tenant market. The same year, it was awarded the Urban Land Institute’s Award for Excellence for Large-Scale New

Community Development, an honor the organization had bestowed on only six other projects in the United States and Canada since

its founding in 1936. By 1986, Las Colinas was home to 600 companies, 50,000 workers and 25,000 residents.

But the bubble was about to burst. Reagan’s tax shelters were replaced with more uniform tax policies in 1986. Inflation

had fallen, taking estate prices down with it. Savings and loans were struggling, and the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex found itself

severely overbuilt. Additionally, pressures within Southland Financial and its subsidiaries were squeezing Las Colinas. Ben Carpenter

would put up a fight to hold on to his dream, but he would soon lose control of it.

Chapter 9: Trouble Visits Paradise

The Carpenter family struggles unsuccessfully to maintain control of Las Colinas

The real estate collapse of 1985 and 1986 was devastating to Las Colinas and the Carpenter family. Ben and his son, John

W. Carpenter III, struggled to save Ben’s beloved project, and they succeeded in part: The Carpenters would eventually lose control

of Las Colinas, but they kept the master-planned community largely intact, preserving its quality, its integrity and its future.

Ben Carpenter’s vision for Las Colinas depended on access to tremendous amounts of cash to service the debt incurred

from land development, land purchases and the monuments with which Ben seeded the development: Williams Square, the

Mandalay Four Seasons Hotel, and the Inn and Conference Center among them. But Southland Financial, Las Colinas Corporation’s

parent company, saw its cash begin to drain away. First, in 1981, Southland had bought out its joint venture partner’s 50 percent

interest in Southland Center in downtown Dallas. The purchase took $30 million from the company’s cash reserves, and extensive

renovations depleted tens of millions more.

Southland Life Insurance, the company Ben’s father, John W. Carpenter, Sr., had built, was a consistent source of capital

for Las Colinas. The Carpenters — as Southland Financial — sold it in January 1984 to the Franklin Life Insurance Company for

$352 million. They used the proceeds to pay off over $200 million in short-term, high-interest loans for land development and

improved properties in Las Colinas. In the fall of 1984, the Carpenters decided to take Southland Financial private, sparking a

scramble for stock that would leave the company further weakened and increase Las Colinas’ vulnerability when the real estate

market ground to a halt a year later.

The Carpenters owned a controlling interest in Southland Financial — approximately 31 percent of the company’s stock.

Ben had always handpicked board members from among his family and friends, and had a reputation for calling the shots, but the

market’s response to his plans to take the company private threatened his empire. First, Dallas businessman Craig Hall upped his

Southland holdings from approximately 5 percent to nearly 10 percent, spurring investor speculation that drove stock prices from

around $20 per share to well over $30 per share. Second, corporate raider Ivan Boesky entered the fray, purchasing nearly 10 percent of the company’s stock, ostensibly seeking a board position and the ability to influence Southland’s future, that is, to

dismantle or sell the company.

The Carpenters’ response was to buy out Craig Hall, at a price that had been inflated by speculation — around $38 per

share, totaling $62 million. The sale brought the Carpenters’ interest to 41 percent and they abandoned the effort to take the

company private. Stock prices began to fall as investors dumped the company’s stock — except for Boesky, who held his shares to

the very end.

It was the family itself — not Southland Financial — who bought out Hall, and they had to sell part of the original

Hackberry Creek Ranch, where Ben and Betty still lived, in order to do it. In a move that proved controversial, in June 1985 the

Carpenters sold 53 acres to a joint venture between Trammell Crow and Southland Financial for $25 million. In 1982, they had sold

113 acres of ranch land to another Southland joint venture, and now they applied the $30 million proceeds to the Hall stock

purchase, taking that money away from much-needed debt service. The family managed to secure Southland Financial, but the effort

had further depleted the company’s resources.

In 1985, Ben added the 2,200-acre Kinwest sector to Las Colinas by buying out the Las Colinas Corporation’s partners in

the Kinwest Development Corporation. To pay for it, Drexel Burnham Lambert was brought in to put together a junk bond deal

valued at $200 million, $80 million of which paid for Kinwest and $83 million was used to refinance land debt.

Meanwhile, the real estate market was coming to a standstill. Las Colinas land sales, which had already slowed, dropped

dramatically in 1985, coming to a halt that fall. By 1986, the entire Dallas area was severely overbuilt. Ben’s Las Colinas landmarks

were draining cash, and debt was climbing. Southland Financial was on the verge of bankruptcy.

In December 1986, Ben stepped down as president of Southland Financial, naming his son, John Carpenter III, as his

successor. Ben’s drive and single-minded focus on Las Colinas had taken its toll on his health. He remained chairman of the board,

but now John, who was in his mid-30s, would handle day-to-day operations.

John’s job was to save the company and Las Colinas along with it — or at the very least, to salvage them. Over the next

three years, John significantly reduced Southland Financial’s debt. He restructured loans and shed the now-unnecessary taxi,

restaurant and retail companies. He disposed of assets, including Williams Square, the Mandalay Four Seasons Hotel and the Inn

and Conference Center. And he looked for a partner to infuse much-needed cash into the corporation and the development.

Lincoln Properties was the first to step up with a serious offer, but it was withdrawn before the deal could close.

Then Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association came forward.

New York-based Teachers, one of the world’s largest private pension funds, had financed several Las Colinas projects,

including several of Ben’s monument buildings. They knew Las Colinas as well as anyone outside the Carpenter organization. They

believed in the development and saw its potential. Eighteen months of due diligence and negotiations with more than 40 parties —

primarily creditors and the Carpenter family — began in December 1987 and culminated in June 1989 with the formation of two

partnerships: Las Colinas Land Limited Partnership and Las Colinas Investment Properties Limited Partnership. Teachers became

the limited partner in both, with the Carpenter family and JMB Realty of Chicago serving as general partners. The new companies

were technically separate, but essentially functioned as one. Southland Financial was dissolved, its shares sold at $2 each, and the

Carpenters traded their holdings for an interest in the new partnerships. The Carpenters were hired to manage the partnerships’

assets, which they did through the newly formed Las Colinas, Inc. and JPI Realty Inc.

Southland Financial’s debt in 1987 was $969 million. The arrangement with Teachers reduced it to $522 million, plus

$246 million in loans from Teachers. Bankruptcy was averted, but all was not well.

In 1989, as the deal with Teachers was being completed, the economy appeared to have bottomed out, and good times

seemed to be around the corner. Exxon and GTE had made major land purchases in Las Colinas. Teachers believed the Dallas

market would soon bounce back and development in Las Colinas would resume at the lightning pace of the mid-80s. The reality was

that no significant growth would be seen in Las Colinas until 1995.

Differences in management philosophies between Teachers and key members of the Carpenters’ management teams led

Teachers to announce in early 1992 that it was replacing the Carpenters as managers. The Carpenters sued, Teachers counter-sued,

and four years of acrimonious litigation later, the parties settled out of court for an undisclosed sum.

Ben sold the family homestead and remaining 56 acres of Hackberry Creek Ranch to GTE in 1999 and moved to Dallas to

be near his children.

At a time when fortunes all across Texas were being lost, Ben Carpenter left behind his dream — a world-class masterplanned

community built on the land he loved. Nonetheless, Las Colinas continues to thrive, sustained by not only by Ben’s vision,

but by the standards — almost unattainably high — that he set as its founder.

Chapter 10: A New Era Begins

1990s are marked by change

In June 1992, as the Carpenters stepped down as managers of Las Colinas, the reins of America’s premier master-planned

community were handed to Faison-Stone, a real estate company that had been formed the year before.

Faison-Stone was a joint venture between Faison, a North Carolina-based real estate company with extensive holdings in

the Southeast, and Dary Stone, a Dallas developer with a background in politics. Stone headed the new company. When Teachers

Insurance and Annuity Association narrowed the search for a new development manager to three firms, two things set Faison-Stone

apart: Henry Faison’s integrity and Dary Stone’s political experience. Las Colinas had benefited from the Carpenter family’s standing

in the community and their ability to move in political circles. Teachers wanted a new manager who could fill those shoes.

Teachers was one of the United States’ largest real estate lenders. In the crash of the mid-1980s, myriad real estate

companies went bankrupt or got out of their equity financing agreements by handing over assets to their lenders. Henry Faison had

never defaulted on a loan to TIAA, even in the midst of one of the country’s worst economic downturns. Teachers recognized his

fidelity and respected his willingness to honor his commitments.

Dary Stone, a lawyer, had served as Bill Clements’ personal assistant in his campaign for governor of Texas in 1978, then

joined Clements’ staff after the election. Stone headed Ronald Reagan’s Texas presidential campaign in 1980 and was Clements’

campaign manager in the governor’s 1982 re-election bid. He also had been Clements’ director of the Office of State and Federal

Relations, Texas’ lobbying arm in Washington, D.C. When Clements lost the governorship to Mark White in 1982, Stone went to

work for Dallas-based Criswell Development Company, overseeing the development of the downtown Dallas landmark Fountain

Place, among other projects.

In 1992, the real estate market was still depressed. In 1997, it began to make up for lost time, and Las Colinas boomed

between 1997 and 2001. More than 6.5 million square feet of office space was built, including projects for Citigroup, Nokia, NEC

America, State Farm, Sterling Commerce, Microsoft and Temerlin McClain. Light industrial space increased by half a million square

feet. Two major retail centers, Las Colinas Village and MacArthur Park, were built, and Las Colinas added 2,000 hotel rooms, including the high-rise Dallas Marriott Las Colinas Hotel on the shores of Lake Carolyn. Still, vestiges of the crash of the

eighties lingered.

Development was disproportionately low within the boundaries of the Dallas County Utility and Reclamation District, or

DCURD, which had built and still maintained much of Las Colinas’ infrastructure. Many developers feared that DCURD’s tax rate

was unstable and avoided the 3,600-acre district, which included much of the Urban Center and some of Las Colinas’ most

valuable land.

DCURD (then Dallas County Municipal Utility District No. 1) was created in 1973 when Ben Carpenter and the Las

Colinas Corporation were the development’s only landowners and the district’s only taxpayers. Ben believed Las Colinas would be fully built out in 15 to 20 years, and counted on continued development to increase DCURD’s tax base and decrease its tax rate. To

allay fears in the meantime, he entered into contracts with 12 commercial property owners, agreeing to pay a set portion of DCURD

taxes, capping the owners’ liability at $.40 per $100 of valuation in most cases.

But the predicted growth didn’t occur. Development halted in 1986, and DCURD’s tax base didn’t increase appreciably

until 1997. Its tax rate doubled in that time, to

$1.50 per $100 of valuation.

Las Colinas Land Limited Partnership

was struggling with the burden of the taxlimitation

agreements it had assumed from the

Carpenters. In January 1998, the Land

Partnership notified most of the companies that

held these agreements that it had terminated

their contracts. The rationale: The agreements

did not carry an end date, and under Texas law,

any contract without a termination date is

considered a month-to-month agreement. The

Land Partnership also filed suit in state district

court asking for a declaratory judgment

rendering the agreements void. All were

subsequently settled out of court.

DCURD had issued capital appreciation

bonds totaling more than $200 million in 1986

and 1989 to restructure much of its debt. The

bonds, which accrued interest, began to mature in 1997, and unless the district’s debt was refinanced again, could cause the district’s tax rate to go as high as $4.00 per $100 of

valuation by 2000.

Headquarters for Dallas County Utility and Reclamation District.

As the boom of the nineties skirted DCURD, a complex plan was developed to stabilize the district’s tax rate. It became

known as the “DCURD global solution” and entailed four major changes, which were pursued simultaneously:

- DCURD, with the required permission of the Texas Legislature, streamlined its tax abatement plan, which had been created in 1995, taking it from a negotiated rate to a standard rate. It also simplified the application process.

- The district restructured much of its $260 million debt through a bond package designed to lower and stabilize its tax rate.

- DCURD petitioned the Texas Legislature to allow the Irving City Council to appoint its board. Since its inception, DCURD’s directors had been elected by the district’s voters, who totaled fewer than 10. This allowed first the Carpenters, then the Land Partnership, to control the makeup of the district’s board. Residential development had purposefully been kept out of DCURD, but its development potential could no longer be ignored. An appointed board now allowed residential development to occur.

- DCURD petitioned the City of Irving to create the Irving Tax Increment Finance District No. 1, or TIF, to reinvest taxes in the district to support development there. The TIF was conditionally created by the City Council in December 1998. In the eight months before it passed in August 1999, the TIF weathered much controversy, bad press and numerous versions of its plan. It passed through two Irving mayors and city councils, the first unanimously supportive, the second at least partially elected on an anti-TIF platform. It was finalized just in time to be approved by two school districts the day before a statemandated rule went into effect barring school participation in TIFs.

The TIF plan allocated $320 million to construct infrastructure to support development and to build four new schools.

It was projected to increase Irving’s tax base by over $1 billion by 2019.

The process of stabilizing DCURD’s tax rate and resolving the Land Partnership’s tax-limitation agreements had a

promising side effect: Las Colinas’ key stakeholders coalesced into a working group with common goals, and the City of Irving made

a renewed commitment to Las Colinas’ growth. Though the DCURD global solution came just before the real estate cycle began its

next downswing, Las Colinas was infused with a new energy that would renew the development’s sense of possibility.

Chapter 11: Renewing the Vision

New land-use plan for Urban Center affirms the spirit of Las Colinas

The real estate crash of the mid-1980s splintered land ownership in Las Colinas. While Ben Carpenter and his Las Colinas

companies avoided bankruptcy, more than 1,000 acres — including several Urban Center tracts — were returned to lenders and

later sold. The Las Colinas Land Limited Partnership assumed stewardship of the development’s master plan, but Las Colinas was

no longer in the hands of one owner.

Ben’s original plan to create quality standards through deed restrictions and protective covenants, then uphold them

through a strong property owners association, stood the community in good stead. Nonetheless, for about 10 years, development in

Las Colinas became more a series of real estate deals than the fulfillment of a unified vision. In 2000, that changed.

The groundwork for the change was laid during the process of accomplishing the “DCURD global solution,” the complex

plan that in 1999 stabilized the Dallas County Utility and Reclamation District’s tax rate and created the Irving Tax Increment

Finance District No. 1, or TIF. While the process was frequently contentious, it fostered dialogue and set the stage for a coalition to

arise that held a common goal for Las Colinas: encouraging new development.

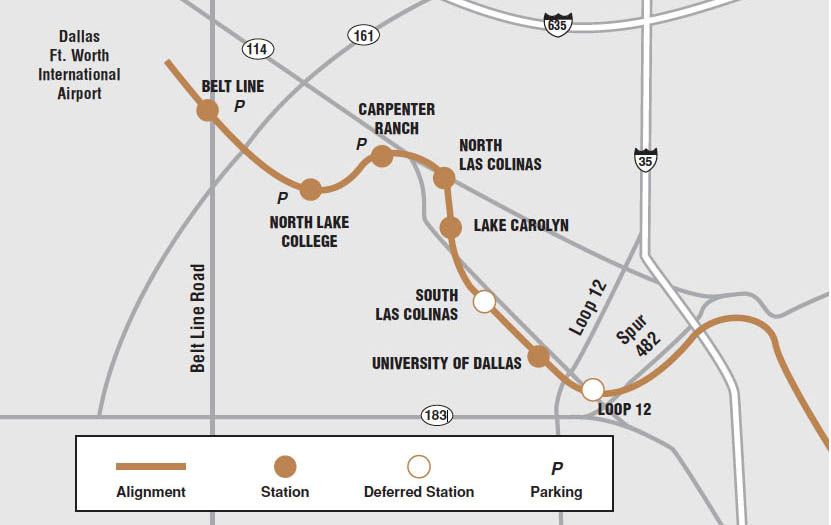

As the DCURD global solution was nearing completion, Dallas Area Rapid Transit was wrapping up its two-year Major

Investment Study of the Northwest Corridor, a broad region of the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex that includes the city of Irving.

A key aspect of the study was the alignment of a light-rail line from downtown Dallas to the Carrollton-Farmers Branch area, which

would also serve Irving. The DART board of directors chose a line that essentially skirted Irving, giving access to only the North

Irving Transit Center by way of a spur from the main line, which would run along Stemmons Freeway.

The City of Irving was committed to bringing light-rail through Irving, not just to the transit center, and pledged $60

million if DART would build a line to serve Texas Stadium, the University of Dallas and Las Colinas before terminating at the north

entrance of Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport. In February 2000, DART agreed with the City’s strategy, on the condition that

the City work with DART to conduct a land-use study of the corridor to be served. The Las Colinas Urban Center, because of its

development potential, was the key focus of the study. Assuming all went well, DART and the City would sign an agreement that

December to build the rail line.

The City wasted no time. In March, it hired

RTKL Associates, an internationally known firm of

architects and urban planners, to begin the study. RTKL’s

team was headed by Paris Rutherford, a young Harvardeducated

planner whose local portfolio included Addison

Circle, Legacy Town Center and Mockingbird Station.

Rutherford took on a project that was ripe for

success: Here was an underdeveloped area at the heart of

an internationally renowned master-planned community.

A budding coalition of stakeholders held a growing

commitment to the greater good of the community, as well

as their own interests. The city government was pushing

for development, and was willing to build the

infrastructure to support it. And a light-rail line was

on its way.

What impressed him most, though, was the

universally shared commitment to Ben Carpenter’s

original vision, a genuine emotional investment in the

spirit of Las Colinas’ master plan. Even when the

stakeholders disagreed on how to accomplish the vision,

they held firmly to the importance of it.

Rutherford held a series of meetings with land

owners and building owners, as well as representatives of

the City, DCURD, TIF and Las Colinas Association. The

meetings were a venue for an ongoing dialogue on development issues: How can Las Colinas’ vision be brought in line with the current real estate market and the needs of developers?

What will the impact on existing properties be? How can a transit-oriented development be created? How can the approval process,

which in Las Colinas is very strict, be streamlined without sacrificing quality?

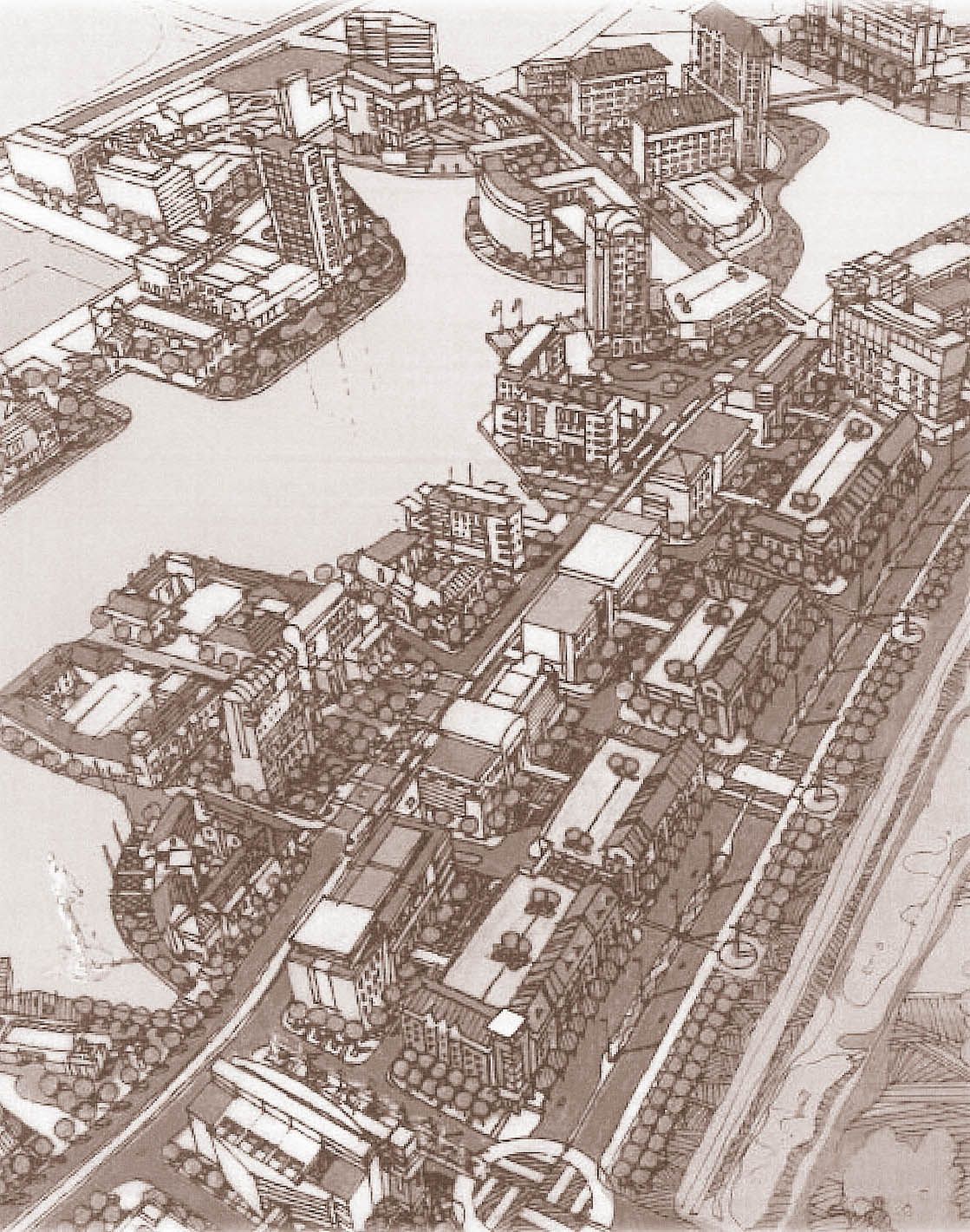

Rendering of the Lake Carolyn transit mall as presented by RTKL Associates.

The plan they created called for a pedestrian-friendly transit mall on the east side of Lake Carolyn, with the light-rail line

running in the median of Lake Carolyn Parkway. The south end of the Urban Center would have two DART light-rail stations, with

one planned to connect with the Las Colinas Area Personal Transit system, which serves several Urban Center buildings. The district

was designed to encourage street life, with pocket parks and a pedestrian promenade around the lake. Development would be

compact and have an urban feel, combining office, multifamily and retail uses. The plan also envisioned a mixed-use entertainment

district across from Williams Square and a “transit village” north of O’Connor Boulevard.

RTKL presented the land-use plan to the City of Irving in November, and it was accepted quickly. DART and the City

forged their agreement in December, as scheduled.

Within months, one luxury loft apartment complex was under construction on the DART light-rail line — even though the

line wasn’t scheduled to open until 2011 — and two more were on the drawing board.

La Villita’s pedestrian-oriented environment features open space, as well as intimate niches.

Northwest Corridor light-rail transit line through Irving to the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport.

Chapter 12: Fulfilling the Dream

Growth surges again, driven by transit, town centers and residential development

Las Colinas is again undergoing a phase of intense growth. But unlike past development surges, this one is driven not by office

towers and corporate campuses, but by residential development, town centers and entertainment districts — many along the path of the

Dallas Area Rapid Transit light-rail line scheduled to arrive in 2011. If even a few of the projects under way are completed, Ben

Carpenter’s dream of Las Colinas as a complete community — a corporate center with residential villages and a thriving urban core —

will be fulfilled.

The first wave of development began in 2004, when La Villita, a 200-acre mixed-use development with New Urbanist

aspirations, broke ground.

After the “DCURD global solution” was completed in

1999, developers were freed from the constraints of the Dallas

County Utility and Reclamation District’s policy forbidding

residential development within its boundaries. In January 2001,

Cousins Properties, which had acquired Faison-Stone, began

master-planning La Villita on land owned by the Las Colinas Land

Limited Partnership. This area, in northeast Las Colinas, historically

had been designated for corporate campus use.

Cousins brought in Andres Duany, a principal in the Miami-based urban planning firm Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company, to begin planning the community. Duany is a pioneer in the New Urbanist movement, a loose organization of urban planners who employ design elements that promote community. They value walking over driving; create public gathering places; design communities on a human scale; and intermingle real estate that is usually separated — homes, shops, restaurants and offices.

While the detailed planning of La Villita was later turned over to Carter & Burgess, a Fort Worth-based planning and

engineering firm, Duany’s New Urbanism took firm hold in the community.

The coalition that arose during the process of updating the Urban Center land-use plan was in place to support the new

development. The City of Irving rezoned the site to allow some of the hallmarks of New Urbanist development: narrow streets, wide

sidewalks and hidden parking — features that create a pedestrian-friendly community. DCURD agreed to maintain the property’s 30-

acre lake, along with its two canals. The Las Colinas Association signed on to maintain the community’s common-area landscaping.

And the Irving Tax Increment Finance District No. 1, or TIF, signed an agreement with Cousins Properties to reimburse significant

infrastructure costs.

La Villita broke ground in January 2004, and has grown almost as fast as its land could be readied for development. Its

success has spurred more residential and mixed-use

development in northern Las Colinas. At least five projects are

under construction or being planned nearby.

In the Urban Center, several large-scale development

projects are under way near the path of DART’s light-rail line.

Three projects are expected to begin construction within a

year, and others are on the drawing board. All are New

Urbanist at heart. Completing any one of these projects will

have a major impact on the Urban Center; together they stand

to reshape the area into a vital, high-density, urban

environment.

Water Street, a town center whose plans include an eclectic mix of trendy shops and restaurants, luxury apartments, office space, entertainment venues and condominiums, is planned across North O’Connor Boulevard from Williams Square. The developers, Urban Partners and Gables

Residential, built Dallas’ West Village and are set to bring the same panache that drove its almost instant success. Taking full advantage

of its long stretch of Lake Carolyn waterfront, Water Street will include a wide esplanade rimmed with loggias — a setting for lakeside

caf s and public gathering places.

Nearby, Icon Partners is developing Las Colinas Station at North O'Connor Boulevard and Lake Carolyn Parkway. Situated

across from DART’s planned Lake Carolyn Station, the project plans hold the highest-density development in the Urban Center: office

towers and residential towers, complemented by shops and restaurants. Leading the project is Icon Partners’ president, Paris

Rutherford, the former RTKL urban planner who led the Urban Center land-use study for the City of Irving in 2000.

Farther north, and running along Las Colinas Boulevard between Northwest Highway and Fuller Drive, the City of Irving and

the Irving Convention and Visitors Bureau are developing a convention center complex and master-developing a hotel and

entertainment district on city-owned land. Set within walking distance of DART’s planned North Las Colinas Station, the project is

expected to catapult Irving into the world of convention-center cities, as well as create a regional entertainment destination.

In December 2005, Las Colinas Land Limited Partnership sold its remaining land, approximately 600 acres, to Hines, a

Houston-based development company. Within 18 months, all but 15 acres were either under development or planned for development,

by Hines, Canada’s Fram Building Group, Lincoln Properties, the Woodmont Company and others.

Once again, the coalition is supporting growth: The Las Colinas Association’s membership in 2006 voted overwhelmingly to

amend deed restrictions to allow town center and residential development in the Urban Center. The City of Irving created a transitoriented

development zone to allow higher densities near light-rail stations, and it has provided incentives for high-quality development.

The TIF has entered into agreements with developers to reimburse selected infrastructure costs.

Las Colinas is known for its high development standards, but the current wave of growth adds a new element: urban style. It

stands to combine the classic aesthetic of traditional development with the cachet of New Urbanism and loft living. Rare is the

community that can accomplish this feat.

In 1973, Ben Carpenter announced his plan for a world-class master-planned community. He laid the groundwork and set

standards high, which sustained his development through the inevitable vicissitudes of the economy and the real estate market, some of